Terry Vaughn was in a race against time.

Back in 2003, a year when he was just beginning to make a name for himself in the American professional referee ranks, he decided to take the DNA test that he knew would deliver an unequivocal verdict: When the result came through it was confirmed he was carrying the gene that triggered Huntington’s Disease, an incurable hereditary disorder that afflicted and killed Vaughn’s father at age 49 along with two uncles and his grandmother.

Vaughn was 30 years old when he learned that it would be only a matter of a few years before the disease would overtake his brain and nerve cells and begin to exact the slow and torturous toll that it does on all its victims, debilitating his mental capacity and leaving him helpless against the uncontrollable muscle twitching that would eventually overcome him.

“Once he got tested, the sense of urgency that he had to do what he dreamed of just became that much greater,” said his wife Kim Vaughn. “He knew he had a shorter window than most – he knew that he had to get it done, and get it done quick.”

The “it” that the Iowa native dreamed of was to be an accomplished referee on soccer’s biggest stages. So with relatively few major match assignments in and around his home state of Iowa, he began traveling extensively, more than most referees did at that age, to build his resume and quickly rise up the ranks before the disease closed in.

Terry Vaughn, second from right holding a match ball, prepares for his first MLS match as head referee. Photo via Kim Vaughn

There was no stopping Vaughn. First came the FIFA badge, then two CONCACAF Gold Cups, a FIFA Under-20 World Cup, plenty of international soccer events and the distinction of becoming one of the first full-time professional referees in US and Canadian soccer history. He worked in MLS for 15 years and was an international FIFA referee until 2011.

"To see your dad [Vaughn's father] go through that and to have the drive and not think about what your life’s going to be like in 10 to 20 years and to live the days and make himself one of the top referees in the United States – heck, in the world – and to have that drive is incredible,” said his friend and former colleague Jerry Cova, who first met Vaughn at an Olympic Development Program camp in 1991. "Not only that, but what he did for Iowa soccer and what he did for the academy and what it does for all soccer referees throughout the region."

“He just really enjoyed refereeing soccer and being around soccer people,” recalls his wife Kim in a conversation with MLSsoccer.com. “Terry would do a major-league game and come home and volunteer to referee our daughter’s Under-8 game, and he had just as much fun in that U-8 game as he did the night before in the middle of an MLS game. That was Terry.”

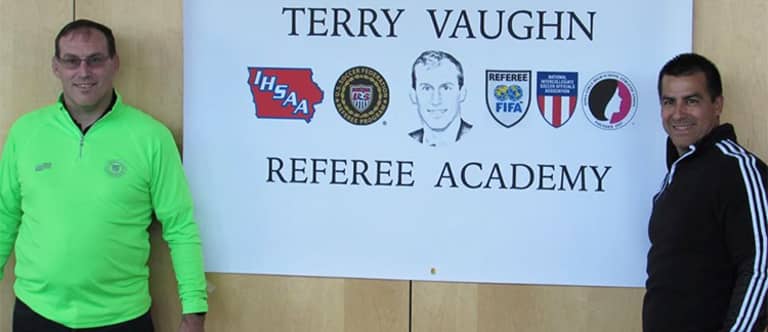

And it was a calling more than a career. In 2002 he founded an annual – and free – education and training convention for young referees in his home state of Iowa, an event that now bears his name: The Terry Vaughn Referee Academy.

“It makes quite an impression on you when you watch old films of him: He ran like a gazelle,” says Kim. “Now, basically he needs a walker just to move to a chair.

“It can be a little overwhelming.”

Terry Vaughn with current MLS referee Ricardo Salazar at the Terry Vaughn Academy in 2016. Photo via Ricardo Salazar

Vaughn's personal battle

Today Vaughn is 43 and even the simplest of physical tasks that most take for granted have become agonizing or downright impossible for him.

Vaughn began to show symptoms of Huntington’s in 2012, and stepped back from refereeing to focus on the battle ahead. It’s been a heavy load for Kim and their 12-year-old daughter Kyla to bear, with challenges mental, physical and financial. One of his primary medications skyrocketed in price from about $5 a month to $5,000 when a patient taking it committed suicide, raising the manufacturer’s liability costs, and the subsequent release of a generic version is only moderately cheaper.

Now forced to spend most of his time in a wheelchair, Terry needs assistance with nearly every aspect of his daily routine, and sometimes struggles to speak clearly.

It’s the Huntington’s Disease fraying the usual connection between the brain and the body. More insidiously, the mind itself is compromised, which can lead to mood swings, personality changes and worse. Research has found that the rate of suicide among HD sufferers is four times that of the general population.

“The muscles start to atrophy because of the twitching. The brain can’t talk to the muscles, with the protein collecting on the brain and the nerve sheets that don’t allow for that communication,” says Kim, who maintains a blog about her experiences with Terry and Huntington's.

The primary medication that helps control Terry’s muscular twitching also inhibits dopamine levels, raising the risk of depression. That in turn has to be counterbalanced by other drugs, leading to further side effects like weight gain.

“It’s tough to see Terry the way he is now compared to what he was, but we know he’s in a battle,” says Cova, who regularly drives up from Missouri to visit Vaughn and his family. “He was a little cocky, but he could back it up.

“The disease is going to take the course it’s going to take,” adds Cova. “But we still see bits of his personality and that’s what draws you to Terry. He’s got an awesome personality and he’s a great guy.”

Terry Vaughn (far left) together with fellow referees Chris Nuzel, Cien Asoera, Tony Vasoli and Kermit Quisenberry at the National Youth Finals in 1997. Photo via Kim Vaughn

Vaughn remains a keen fan of the beautiful game, watching as much MLS and other soccer as he can and often asking Kim or Kyla to send text messages of support to his friends in the refereeing ranks. He also takes comfort from regular servings of ice cream, a lifelong passion that now also helps balance some of the side effects of his medication.

“He was always very happy-go-lucky,” says Kim of Terry. “But when he started to go through his depression, he turned into somebody that was pretty angry a lot. We didn’t know at the time, but that was the Huntington’s affecting his brain. Not only was he depressed, he was angry, he was moody – he really didn’t know what to do with himself. It was pretty overwhelming to him because all that he knew was sliding through his fingers. He had some pretty dark moments.”

The fight continues

Vaughn is one of more than 30,000 people across the United States who are suffering from Huntington’s Disease. Another 200,000 Americans are considered at-risk due to their genetic profile.

“One of the things that’s so devastating about this disease is that nobody wants to talk about it – and I have to raise my hand because I was the same exact way,” Kim Vaughn says. “Because you know fairly early on, with the DNA tests that are now available, whether or not you’re going to get the disease. And it’s pretty easy to bury your head in the sand and not have a conversation about the disease, because of the depression and the anxiety that comes with it.”

May is Huntington’s Disease Awareness Month, and in solidarity with Vaughn and other sufferers, his former coworkers in the Professional Referee Organization (PRO) are wearing blue wristbands stitched with the letters "HD" during match play (a smaller version is available for sale here).

It’s an important opportunity to build awareness about a disease that remains unfamiliar to many, and an emotional nod to one of the refereeing profession’s respected veterans.

“Terry was always the biggest supporter of his crew during the game,” says Vaughn’s longtime friend and colleague, Kermit Quisenberry, who currently serves as an MLS referee. “You had the confidence that he was going to support you through thick and thin.

“We call this a brother-and-sisterhood, and that’s exactly what we [referees] are. I’m still getting text messages and phone calls from people wanting to get some of the wristbands, from California to New Hampshire to Florida to Las Vegas,” he adds. “We support each other both on the field and off the field as well … When someone falls, everyone rallies around them, even if they might not know the person. It’s the type of community we are.”

Others have joined in too, like television commentator and former MLS player Brian Dunseth.

“I have a ton of respect for how he went about his job,” says Dunseth of Vaughn. “Terry was a very good man off the field who treated people with the utmost respect.”

The Huntington’s Disease Society of America has coined the phrase #LetsTalkAboutHD to spread the word, and for Kim it’s a fitting slogan.

Terry Vaughn, in wheelchair on left, joins family and friends in a HDSA walk to raise funds for research. Photo via Kim Vaughn

The family has seen great improvements in the treatment of HD since Terry’s father went through it. Although it likely won’t be able to help Terry, an ongoing study in Great Britain has found promising results with a new drug, ISIS-HTTRx, that appears to reverse some HD symptoms.

The Vaughns consider themselves fortunate to live in close proximity to one of the Huntington's Disease Society of America’s “Centers of Excellence,” and urge those interested to donate to HDSA, which holds walkathons and similar fundraising events around the country.

“All of that money goes to fighting the disease and doing the studies for those drugs,” says Kim. “People can support that – that’s the best place for those dollars to go, because they know what it takes to fight the disease.”

You can donate to help Terry Vaughn's family with their medical expenses in his battle with Huntington's Disease or donate to the Huntington's Disease Society of America.